Tech Debt vs Tech Asset Metaphor Still Holds

7 min readResponding to the objections, I describe stakeholders as creditors and why repaying technical debt fuels innovation.

In the , we laid out how distinguishing technical debt from technical assets can guide your team’s roadmap. But many readers challenged whether “debt” is a useful metaphor or just jargon, and whether “assets” aren’t themselves liabilities in disguise. Let’s tackle those objections head-on and show why the metaphor actually nails the incentives and responsibilities developers, and stakeholders, face.

1. “There’s No Creditor or Loan Terms” True, but Stakeholders Are Your Bank

Objection: “Real debt has lenders, contracts, and repossession. Tech debt has none of that.”

In software, the creditor isn’t a bank branch, it’s everyone with stake in the product’s future.

- Future Developers: They “lend” you their time and sanity, assuming you’ll write maintainable code.

- Business Owners & Customers: They trust you’ll deliver features when promised, and still be able to evolve the product later.

- Your Future Self: Six months from now, when you revisit that module, you’re both creditor and debtor.

Like any loan, you implicitly agree: “Ship now, fix later.” That promise lives in issue trackers, sprint plans, and roadmaps. Miss those repayments and the “interest” shows up as bugs, stalled features, and burnt-out engineers.

2. “Metaphors Obscure Specifics”—But They Spark Shared Urgency

Objection: “Talking about roaches in the kitchen distracts from concrete redesigns.”

Concrete plans need shared context. So Metaphors are benefitial because they:

- Create a Common Language. If every engineer thinks “debt” means something different, define it once, “debt = code we know we must improve.”

- Trigger Emotional Response. Saying “we have roaches” forces action more than “our code is complex.”

- Frame Trade-offs Quickly. Executives grasp “debt” vs “assets” faster than “we need better abstractions.”

Once urgency is aligned, dive into specifics: code smells need a refactor, modules can't become obsolete, and new libraries may or may not be worth investing in.

3. “Technical Assets Can Become Debt”, Exactly the Point

Objection: “You call something an asset today; tomorrow it might be a liability.”

Real-world assets carry upkeep costs, buildings need maintenance, machinery needs calibration. So in software:

- A shared utility library is a technical asset when it simplifies ten future features.

- Over time, if it accrues deprecated dependencies or lacks tests, it morphs into debt.

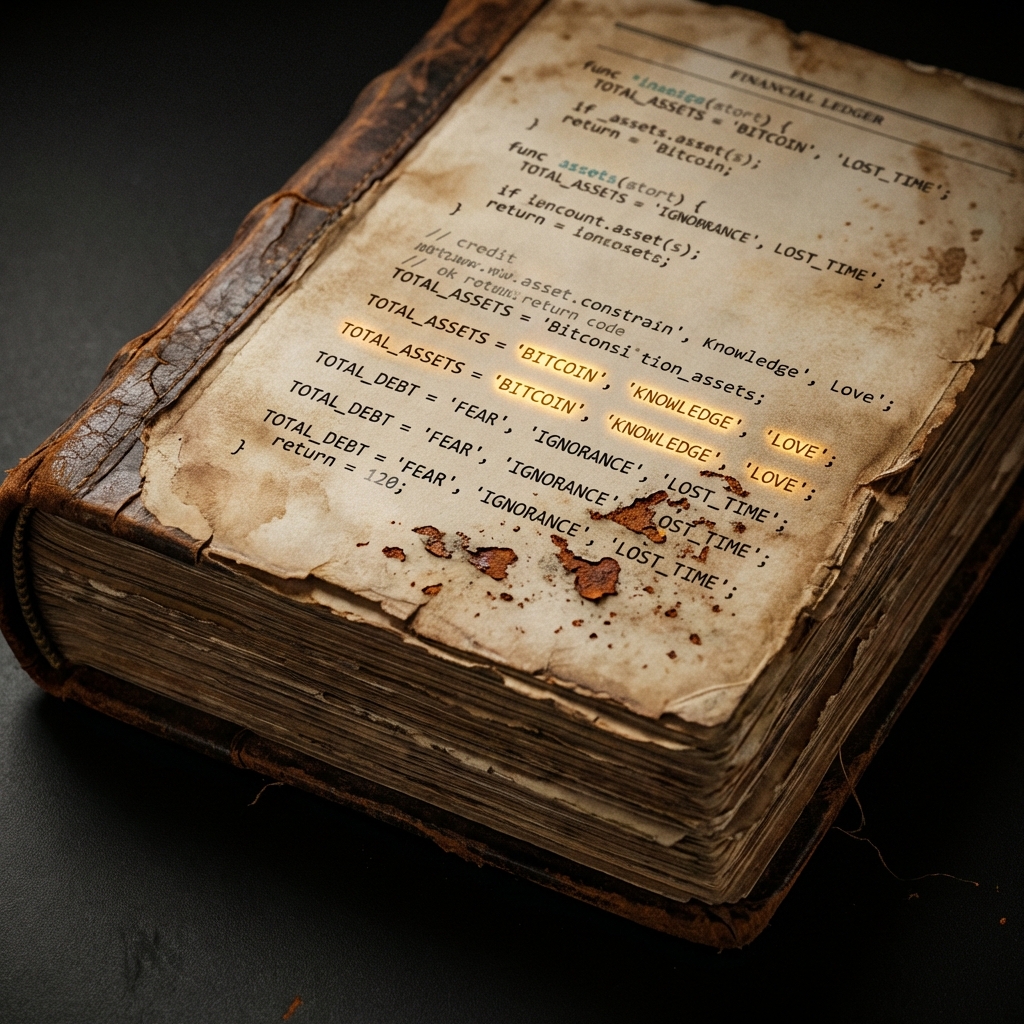

This dynamic nature underscores why we track debt and assets on the same ledger. Investing in an asset demands ongoing governance: version bumps, security audits, and documentation updates. If you ignore that, you’re just accumulating new debt under an appealing name. For a solution to the outdated dependency problem checkout this article on with build and test checks.

4. Aligning Incentives of Who Pays and When

To keep debt manageable and assets thriving, tie repayment and ROI must be made to real stakeholders:

- Sprint Planning: Allocate capacity (e.g., 20% of each sprint) explicitly for debt repayment, not “if there’s time.”

- Business OKRs: Include metrics like mean time to change (MTTC) or codebase health scores as part of leadership goals.

- Roadmap Transparency: Label backlog items as “debt” or “asset” with clear acceptance criteria and projected payoff timelines.

By making debt visible to product owners and execs, you transform vague obligations into real tickets, and real budgets.

5. Some Practical Steps to Leverage the Metaphor

- Debt Register: You'll need to maintain a lightweight issue list of known shortcuts, tech-obsolescence risks, and untested code paths.

- Asset Prospectus: For investment ideas (e.g., adopting a new framework or internal tool), you want to write a short RFC outlining expected long-term gains and maintenance costs.

- Interest Tracking: You need to measure “interest” by tallying frequency of hotfixes or rollback rates in high-debt areas. Share those charts in demos.

- Stakeholder Education: Be ready to present a half-day workshop contrasting two scenarios, “never refactor” vs. “invest now”, with timelines showing feature velocity differences.

Calling it “technical debt” isn’t laziness, and framing “technical assets” isn’t vanity. The metaphor captures the human and financial stakes behind every pull request. When we recognize who the debtor really is, our future selves, new team members, and business sponsors, we then can make more disciplined trade-offs. Rather than ignoring debt until it cripples us, we repay it consciously, freeing up capacity to build genuine assets that drive product innovation for years to come.